Note: This post is a bit of a departure from what you normally see on the AlmaLinux blog, but we would love to share more stories like this! If you would like to write a post about how AlmaLinux helps you in your daily life, reach out to benny.

The College of Letters and Science at the University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB) uses AlmaLinux, among other Linux distributions, in regular day-to-day operations. One such use case for AlmaLinux is the build infrastructure behind data science environments that serve hundreds to thousands of students per term.

Jupyter at UCSB

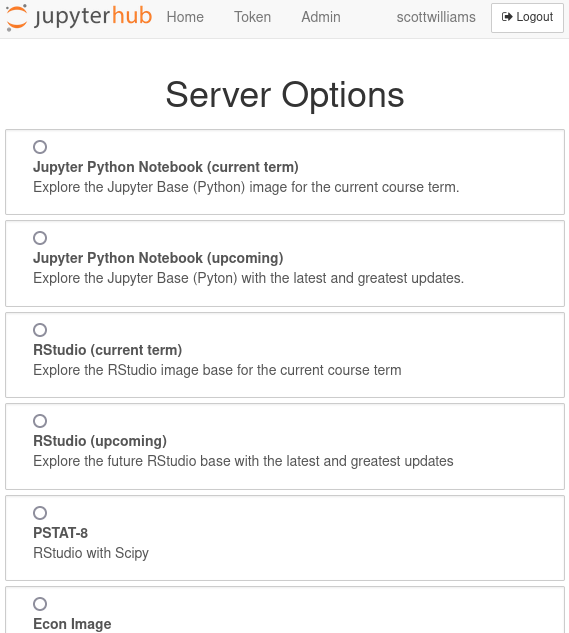

Jupyter is used extensively at UCSB for classroom and research environments supporting Python and R language-driven research and curriculums, across such broad disciplines as data science, economics, linguistics, physics, psychology, and earth sciences. Traditionally, Jupyter and RStudio environments were either done in lab environments or on student machines. Unfortunately, this led to significant fragmentation of versioning and technical debt. Before long, machines were running old versions of things and were one well-meaning pip install or install.packages() away from fetching a library that was no longer compatible with older versions of the software. This means that student environments were easily broken, and TAs had to spend time fixing them and students sometimes had to learn on older, outdated versions of Python, R, and Jupyter.

The solution to this was to move to JupyerHub, deployed on Kubernetes, using Zero To JupyterHub as a resource for getting things started. Over time, the deployments themselves began to be standardized via Terraform with configs being tracked in git repos. Yet, while the deployments themselves became more manageable in this way, maintaining the images themselves was another problem. Often, each course had its own, often complex, requirements regarding libraries, extensions, and versions, and without a standardization on image bases. The technical debt of the lab environments ultimately found its way back in the form of container image sources that were now shipping the older versions. While still incrementally better (in that an updated Python library now keeps an image from being built rather than breaking a production lab environment or student machine’s instance), this solution still meant potential for deploying vulnerabilities that were now being served over the public internet and didn’t solve the problem of courses and research getting stuck on outdated versions.

As more and more faculty turned to us to deploy Jupyter environments, the layers of complexity made things harder to maintain.

Continuous Integration (CI)

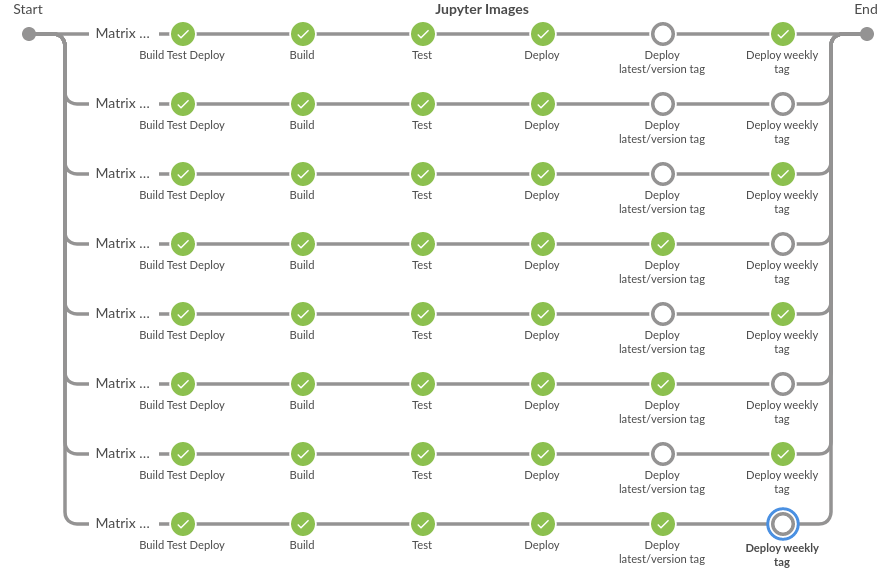

While there were some early attempts at automation of the images via GitHub Actions, ultimately something more powerful became necessary and Jenkins was leveraged to bring things under control. The first priority was getting old images simply working again, even if by messy means. Some of these images took over an hour to build on a new Ryzen 7 development laptop and had inconsistent break points making attempts to fix broken images an incredibly tedious and time-consuming process, especially when updates were needed with a quick turnaround for an ongoing production course. The time spent to generate a simple Build-Test-Deploy style Jenkinsfile very quickly paid for itself as the builds could be delegated to more powerful server hardware, making the feedback loop far more efficient and freeing up developer hardware to focus on working on the next incremental step, while the building and testing were handled by designated hardware (in this case, EPYC Gen 2 machines running AlmaLinux 8).

Once the immediate emergencies were remedied, work began on standardizing on a common image base. Previously, some images were based on old 3rd party upstreams, some were based on an outdated Microsoft platform, some were based on old Jupyter images, and some were totally custom. There had been some prior attempts to make a common internal base, but without a proper and predictable CI, it ended up adding to the chaos.

Jupyter produces its own upstream images and they are regularly updated. It made sense to use Jupyter’s upstreams directly, but we could not do it with the old methods for image building. If we were going to do it right, we needed to go all the way. We created new base images for Python, SciPy, and R based on Jupyter upstream images and made all course images be based on these bases. These base images, which are public and open source, are built, tested, and updated against the upstream Jupyter images at least weekly in addition to the latest Jupyter version standardized on for the current term, and include common libraries and extensions used across the majority of courses in addition to what Jupyter provides.

On successful build, all downstream course images are then rebuilt, tested, and published to Docker Hub (regardless of whether the course image is currently being used in production or not), so that we know about surprises when they happen and before they cause an issue with a deployment. Additionally, there is now a test site for current and future versions that faculty and TAs can access to test their stuff even before their course is deployed that is perpetually kept updated with images shipped from the Jenkins.

As any change does, this move also required a cultural change. Instead of faculty or TAs curating their own images and being concerned about low-level details, we now ask them to define their dependencies and we curate them on their behalf, writing tests against each one. As a pleasant surprise, this change was an overall welcome one as faculty spent less time worrying over the technical details under the hood of Jupyter and got to enjoy current versions of the software. The Jupyter offerings are now even more popular than ever as a result!

AlmaLinux

All of the move to a CI-driven process was an attempt to cull technical debt by identifying variables that might cause issues in production before they reach production. Given the inherent complexity of CI systems, and especially fully featured ones like Jenkins, there is always a risk that significant time will be spent on keeping the CI engine itself afloat. In order to limit the variables of surprises in the CI system itself, we needed a predictable platform for the workers that are actually doing the building, testing, and deploying, so that when builds or tests fail, there is confidence that it is because there is a problem to be solved and not a surprise environmental change on the workers. For this reason, AlmaLinux was chosen to run bare metal on the EPYC Gen 2 servers powering Jenkins. These AlmaLinux servers now build and test (with Podman) and then deploy (with Skopeo) every image we currently maintain in Docker Hub for these environments.

As time went on, this system had proven itself invaluable. The time to launch from each request was a mere fraction of what it was before and with far better quality deployments. In looking to the future, anticipating that ARM may be an eventual reality, we acquired three Raspberry Pi 4 8GB model B units and have begun incorporating these into regular builds, including the regular python and scipy base images for both current and integration testing streams. These are running AlmaLinux 9 and build in parallel to the EPYC x86_64 AlmaLinux servers on builds where they are currently enabled and are also published to Docker Hub alongside the x86_64 images.

Ultimately, the stability and versatility of AlmaLinux made it an obvious choice, since whether it runs on new, high-end EPYC servers or on significantly less capable Raspberry Pis, it is easy to deploy and predictably reliable.

— “These statements are my own, not those of the Regents of the University of California. References or pointers to non-University entities or resources do not represent endorsement by the Regents of the University of California.” - Scott A. Williams